I have recently had to study some models that use fractional derivatives, which I knew nothing of before. Turns out, these are a lot of fun, and deserve their own post. The notion was apparently already formulated by Leibniz, but there were difficulties involved that kept it from being widely used (such as being, well, bloody difficult). We’re mostly going to ignore those and dive in as if this is a normal thing for a human to do. I want to thank the excellent video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4sTAKN6yFA for introducing the topic to me this way.

The basis of the idea is simply that the derivative of the integral is the function itself, or

(I’m simplifying here, so just assume that the function has all the nice properties to make this possible). Of course, we will need this to hold for higher orders as well. If we denote by the function obtained by integrating

n times as follows:

Fortunately, iterated integrals are not a problem, thanks to the Cauchy integral formula (the other one):

Remembering that , we see there is nothing in the above expression that cannot be generalised to any positive real number (we’ll stick to these for now, lest we get lost too early). Supposing

, we define

There’s a bit of a problem. here regarding integrability. For instance, if you take , the above does not work. Instead, we cheat a little by making the lower bound finite:

We lost uniqueness here, since now we also have to specify the constant used, but we gain the ability to integrate more functions this way. So, we have a fractional integral, but how do we get to the derivative? By remembering the above relation between derivative and integral, we can set

If you look at this informally, you’ll see the derivatives and integrals “cancel out”, except for the integral of order , which indicates that this is a derivative of order

.

This particular approach is called the Riemann-Louisville derivative, and it’s not the only one. In fact, there are several definitions of the partial derivative using different kernels – and they’re not equivalent. For the moment though, I think this one illustrates the point well enough, so let’s suspend looking at the others. To see how this would work, let’s compute the -th derivative of a simple function, say

, and see if it makes sense. Since the first derivative is

and the second is the constant 2, the

-derivative should in some sense be “between” these two functions. From the definition, we have to compute

According to our definition, we now need to find

is easy enough to compute (use a substitution to turn it into a Gaussian) and is equal to

. The rest of the integral is not too difficult either – just use the substitution

. This gives us

To check our integral, we do it numerically in Python with the script

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import scipy.integrate as integrate

def fun1(t,a,x):

return (1/np.sqrt(np.pi))*(t**2)/np.sqrt(x-t)

def int0(a,x):

return integrate.quad(fun1,a,x,args = (a,x))[0]

def check(t):

return (1/np.sqrt(np.pi))*16*(t**2.5)/15

xspace = np.linspace(1/100,1,1001)# - (5-1)/100,101)

valspace = []

for j in xspace:

valspace.append(int0(0,j))

valspace0 = check(xspace)

plt.plot(xspace,valspace0, label = 'Int')

plt.plot(xspace,valspace, label = "Num")

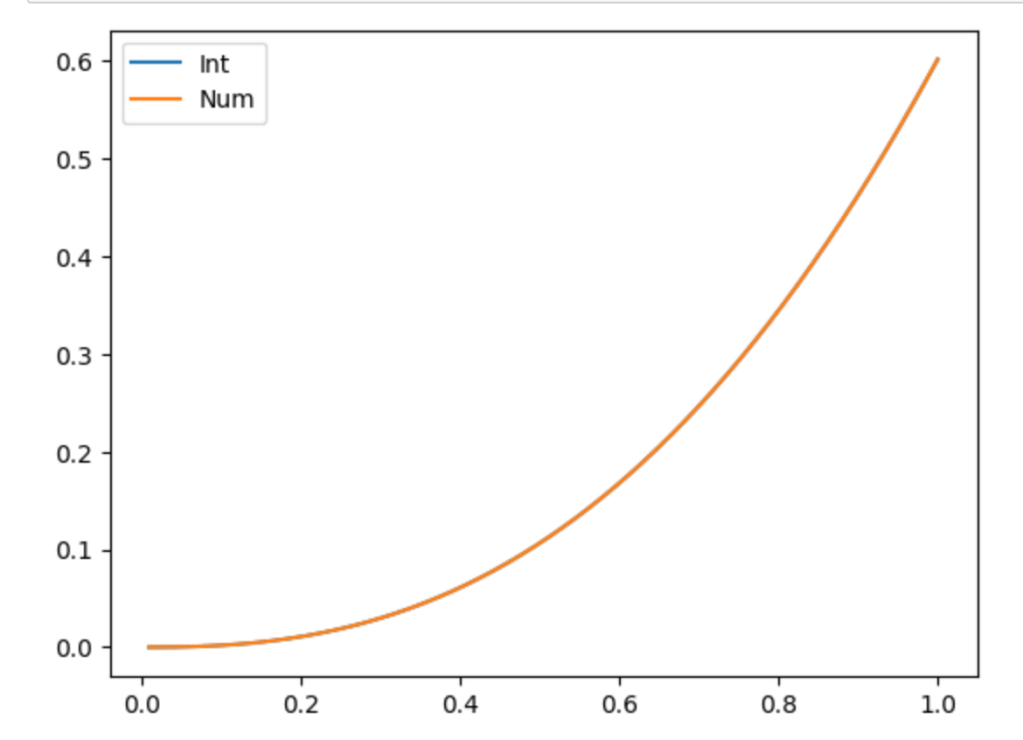

plt.legend();This gives us the following figure, where only one function can be seen, because the two fit snugly on top of each other.

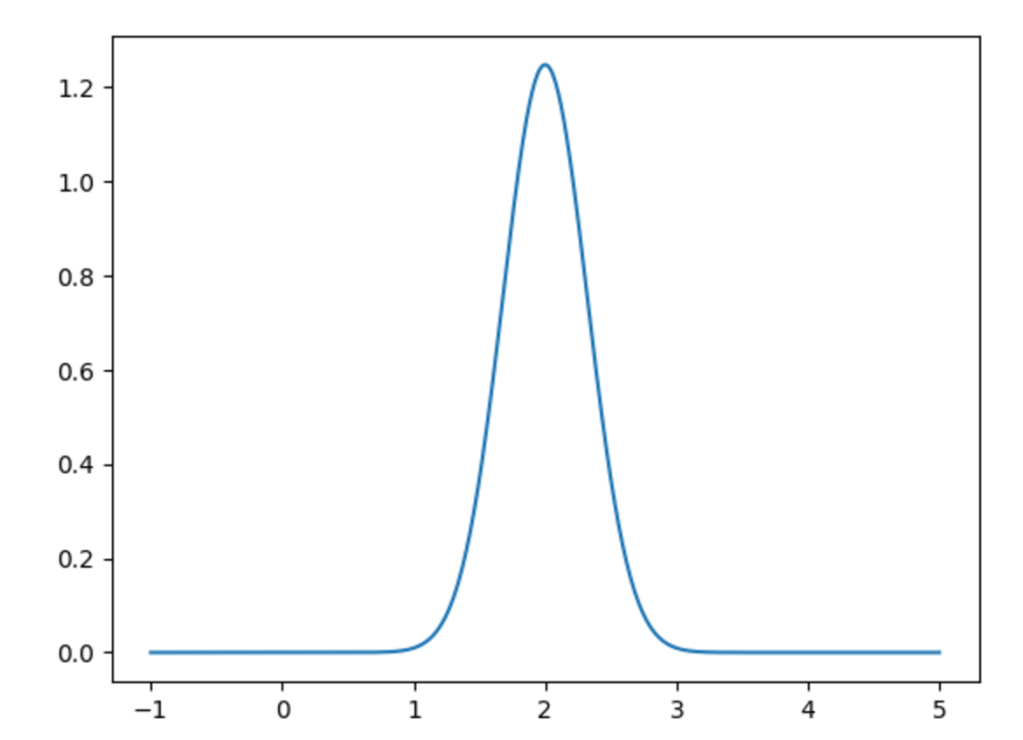

Now that we have some confidence that we’ve evaluated the integral correctly, all we need to do is take the derivative twice to get to the desired 3/2 fractional derivative:

Still, does this make sense? There are certainly some intuitive rules that should be followed by our fractional derivative, namely that it should be somehow sandwiched between the integer derivatives, and that there should be a continuity here: we would expect the 0.75th derivative to be closer to the first derivative than the 0.5th one, for instance. Since I don’t want to do an extra bunch of integrals, let’s numerically differentiate some integrals like the above and see if we get closer to the first derivative. But since this post is getting out of hand, let’s leave that for the next one…