Dedicated to the memory of Willem L Fouché who, amongst many other stellar contributions to my life, told me to go read Dym & Mckean, and also taught me the connections between Fourier analysis and descriptive set theory.

It’s all well and good to learn advanced mathematics because it’s interesting to you or useful. Not everyone is interested in the history or origin of a field, and that is perfectly fine. For myself, I do not feel I fully understand something until I have some sense of how it originated and more importantly, why. I occasionally discuss Fourier analysis on this blog, because I think it is kind-of magical and because I feel like I don’t have a deep, intuitive understanding of it yet. Recently, I’ve been considering the question whether Fourier analysis was inevitable. Without necessarily going back through the historical record in detail, what would be my guess as to how it came about? This post should perhaps be regarded as historical fiction – an account of how things might have happened.

Since little (but not nothing) happens in a vacuum, let us start with the heat equation, which – as we’ve established – Fourier was obsessed with. Without giving initial or boundary conditions then, we’re looking at the equation

when we’re only considering one dimension.

How do you solve a problem in mathematics? By some combination of two things:

- Solve an easier but related problem, or

- breaking it up into bits you can solve.

We’ll use this combination to try to puzzle out how Fourier analysis could have come about.

The heat equation is not difficult to get a general solution for, if we leave out the initial and boundary conditions. By separating variables and setting , we get

.

Since the first two parts depend on different variables, they need to be equal to a constant. Using a minus sign in front of is a bit of a cheat, anticipating the form of the solution, but it will make things easier. We can then see that the following function is a general solution:

Of course, this works for as well, and we can multiply by arbitrary constants without breaking the solution, so we have

Now, a differential equation usually isn’t much use without some initial and boundary conditions, so let’s suppose we’re looking at something (a rod, perhaps) of unit length, whose ends are kept a zero degrees:

To ensure this is satisfied, we can set and replace

by

. This would break our solution, if it weren’t for the fact that we can compensate for it by adjusting

, which we are free to do. (Some members of the audience are screaming out that I’m missing a whole bunch of solutions – don’t worry, we’ll get to it!)

It’s going well so far, but what about the initial conditions? This is where it gets interesting. But making it too interesting makes it very difficult, so let’s start with the easiest possible case. Since the initial condition is given by

we surely can’t get any simpler than setting . The problem is solved! At least, as long as we can set

, which we can do because it was, after all, arbitrary. Unfortunately, things usually don’t stay this simple, but let’s make it incrementally more difficult. What if

(We only take integer multiples in the argument of since we still have to satisfy the boundary conditions.) That’s absolutely no problem, either. The sum of two solutions is still a solution (because our differential equation is linear), so we can solve separately for the two terms and just add them, with the new frequency involved adjusted for in the coefficient of the term. We can do this for any number of terms. In other words, we can solve the problem for any initial condition of the form

Great! We’ve solved the problem for a whole class of functions. The question becomes: exactly how big is this class? And can we use this method to expand this class?

Fourier’s audacity was to say that, if we allow to be infinite, all functions can be written this way. Now, this isn’t exactly true, and much of Fourier analysis has focused on finding out specifically how true it is, and more modern notions of convergence are necessary to even frame the question properly (back in Fourier’s day, they played a bit fast and loose with these issues). Certainly, most “nice” functions on the unit interval can be written this way, meaning the heat equation is solved for all of them. That is a great accomplishment!

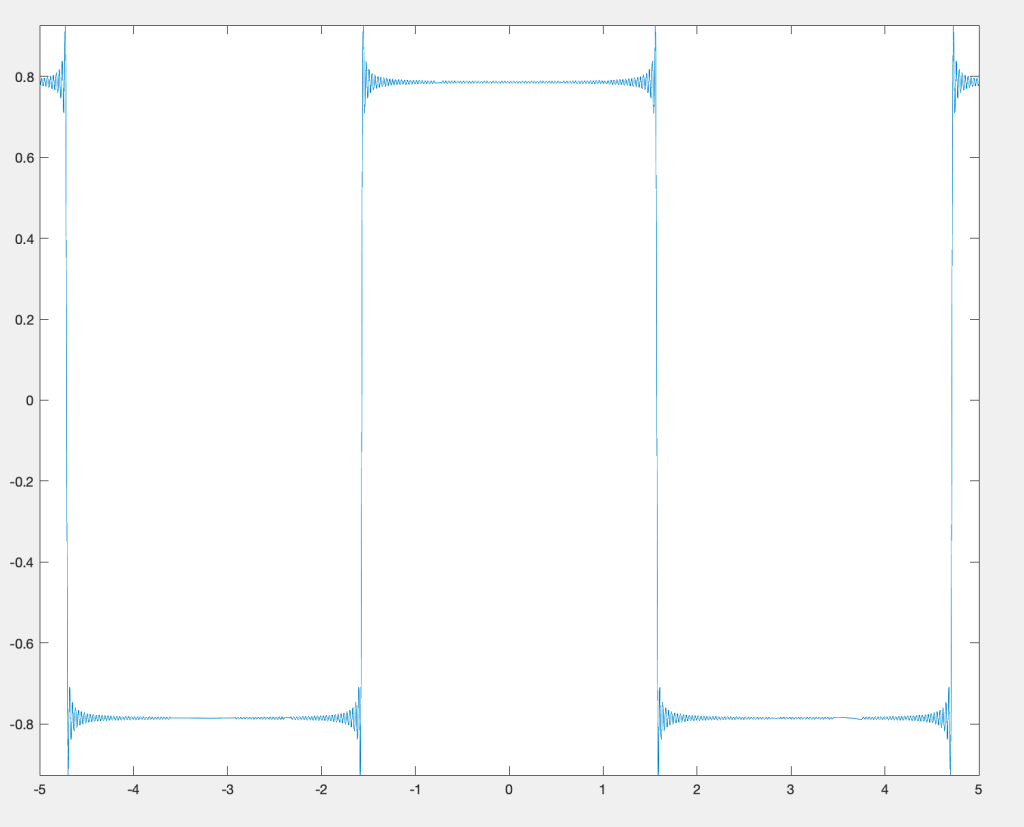

Fair enough, but this part of the story is still not obvious. Perhaps Fourier had a suspicion that functions can be expanded as sums of trigonometric functions, but how do you go about verifying that? I can only imagine that an enormous amount of work went into this. Nowadays, it is the work of a few minutes to write a script that will output the visualization of a trigonometric sum of the above type. In Fourier’s day, this all had to be done by hand. This might seem like a disadvantage, but I’m not so sure. You would need to think deeply on what you would spend your time on, and choose your problems with care. I’m not against the widespread use of computing in mathematics, but I do think we can learn something from the work habits of the old masters.

So, we can assume that Fourier (like his contemporaries) was an absolute wizard at calculus. If I had to reconstruct his thought process – albeit through a modern lens – I would imagine it went something like the following.

Fourier didn’t have function spaces and orthonormal bases to play around with – even the basic concepts of set theory were still decades away (and Fourier analysis played a crucial role in Cantor’s work, too). But he probably would have been exquisitely aware of the following integral:

and

If we now take the trigonometric series as given above, we can say that

Using the identity above, we can conclude that

In other words, if we assume that is a linear combination of “nice”

terms, we can recover that linear combinations by “projecting”

onto each term. If we assume that

can be infinite, and that any function (appropriate to the boundary conditions) can be written as such an infinite linear combination, we have a way of finding each coefficient. This means that if we are able to disregard a whole mess of convergence issues, we can solve the heat equation for a very wide range of initial conditions. To make this more general, we can do something very similar with

, which will allow us to handle other conditions.

Of course, the mathematical world did not immediately accept Fourier’s methods, with good reason. A lot of work remained to be done. Even today, the convergence of Fourier-type series is an active area of investigation. I can imagine that those who had to use the heat equation in practice welcomed this advance, though. Indeed, it was only a short while before the consequences of this stretched far beyond application to the heat equation…