Previously, we managed to get an idea of the justification of using convolution by using probabilities, and it seems to make some kind of intuitive sense. But do the same concepts translate to Fourier analysis?

With the convolution product defined as

(where we leave the limits of integration up to the specific implementation), the key property of the convolution product we will consider is the following:

One possibility that immediately presents itself is that, if the Fourier coefficients of and

are easy to compute, we have a quicker way to compute the Fourier coefficients of the convolution, which doesn’t involve computing some ostensibly more difficult integrals. Which requires us to answer the question: why do we want to calculate the convolution in the first place?

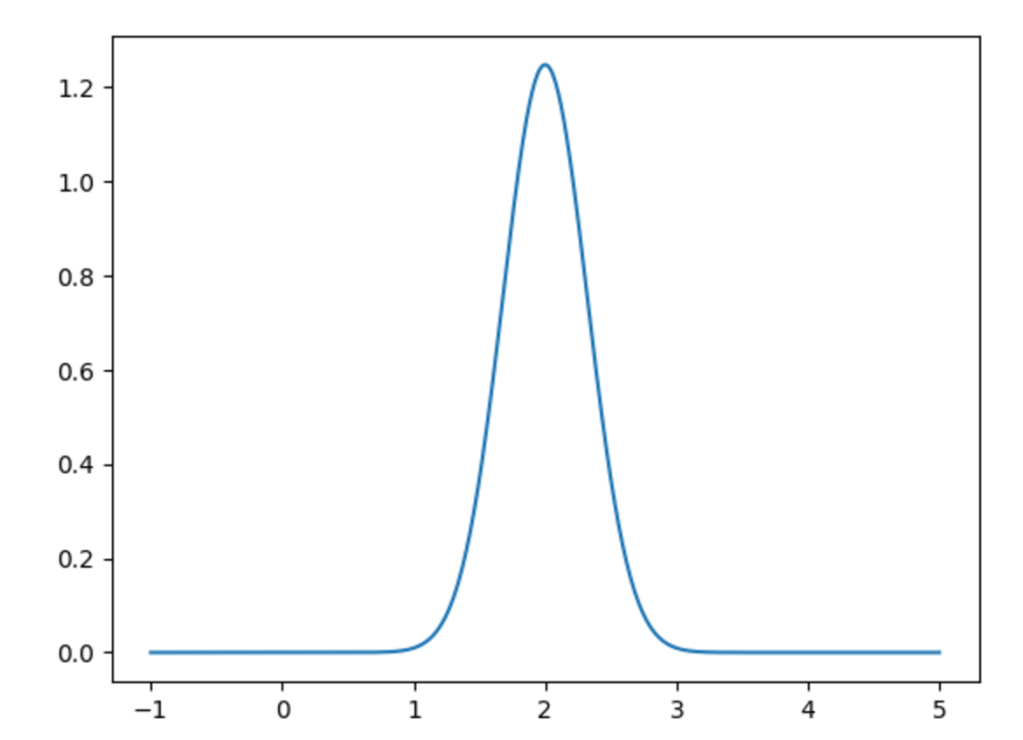

Let’s take some easy functions and see what happens when we take the convolution. Let

The Fourier coefficient of these functions are really easy to compute, since we have

and

meaning that ,

,

and

. This implies that

This allows us to immediately write down the convolution product:

Clearly, our two signals modify each other. How is this significant? The best way to think of this is as an operation taking place in the frequency domain. Suppose is our “original” signal, and it is being “modified” by

, yielding a signal

. The contribution of a frequency

to

(in other words, the

-th Fourier coefficient), is the

-th Fourier coefficient of

multiplied by the

-th coefficient of

. We can see this as a way of affecting different frequencies in a specific way; something we often refer to as filtering.

We often think of the function in the time domain as the primary object, but looking at the Fourier coefficients is, in a way, far more natural when the function is considered as a signal. Your hear by activating certain hairs in the inner ear, which respond to specific frequencies. In order to generate a specific sound, a loudspeaker has to combine certain frequencies. To modify a signal then, it is therefore by far the easiest to work directly on the level of frequency. Instead of trying to justify the usual definition of convolution, we see the multiplication of Fourier coefficients as the starting point, and then try to see what must be done to the “original” functions to make this possible. So, we suppose that we have made a new function that has Fourier coefficients formed by the product of the Fourier coefficients of

and

, and try to find an expression for

:

If you simply write out the definitions in the above, and you remember that

when

,

you will get the expression for the convolution product of and

. As such, the definition of convolution has to be seen as a consequence of what we would like to do to the signal, rather than the starting point.

We still have not related the definition to how convolution originated in probability, as detailed in the previous post. Unfortunately, the comparison between the two cases is not exact, because in the probabilistic case we obtain a completely new measure space after the convolution, whereas in the present case we require our objects to live in the same function space. Again, the solution is to think in frequency space: to find all ways of getting , we need to multiply

and

for all values of

, which leads to our definition.

(As always, I have been rather lax with certain vitally important technicalities – such as the spaces we’re working in and the measures – such as whether we’re working with a sum or an integral. I leave this for the curious reader to sort out.)