One thing I didn’t know about Fourier was his obsession with heat – and not just in the mathematical sense. He literally thought that heat was some sort of panacea. So much so that it contributed to his death! See https://engines.egr.uh.edu/episode/186, for instance.

So, we have the heat equation. How do we solve it? More importantly, how did Fourier solve it? This is somewhat difficult to ascertain, in the general form, for Fourier’s book is written in a manner different from what is today accepted as a mathematical text. First of all, there are many more words and lengthy physical explanations – Fourier’s aim, after all, was not to promulgate a mathematical theory, but a real and useful way of solving the problem of heat in many bodies under many conditions. Of course, we also cannot expect a book from the early 19th century to adhere to our standards of mathematical rigour.

Fortunately, I have come across a great book which starts off with Fourier’s approach to the heat equation, namely “Hot molecules, cold electrons” by Paul J Nahin. If you haven’t read any of Nahin’s books, do yourself a favour. He’s an electrical engineer with a keen appreciation for mathematics, and he makes it a lot of fun. Over the next few posts then, since we’re exploring the origins of Fourier analysis, I thought I would present an argument by Fourier that is recounted in Nahin’s book. I’m not going to go into too much detail, because working that out is part of the fun.

What Fourier was so very good at was solving problems by representing functions as infinite series. It does not seem at first that this would make things simpler, but it does – a lot. Many (including Laplace and Lagrange) were skeptical of Fourier’s methods, and honestly, the techniques did not exist yet to fully justify the methods. Nevertheless, Fourier knew they worked, and he became a titan of mathematics because of them. Here, we will look at his proof for the identity

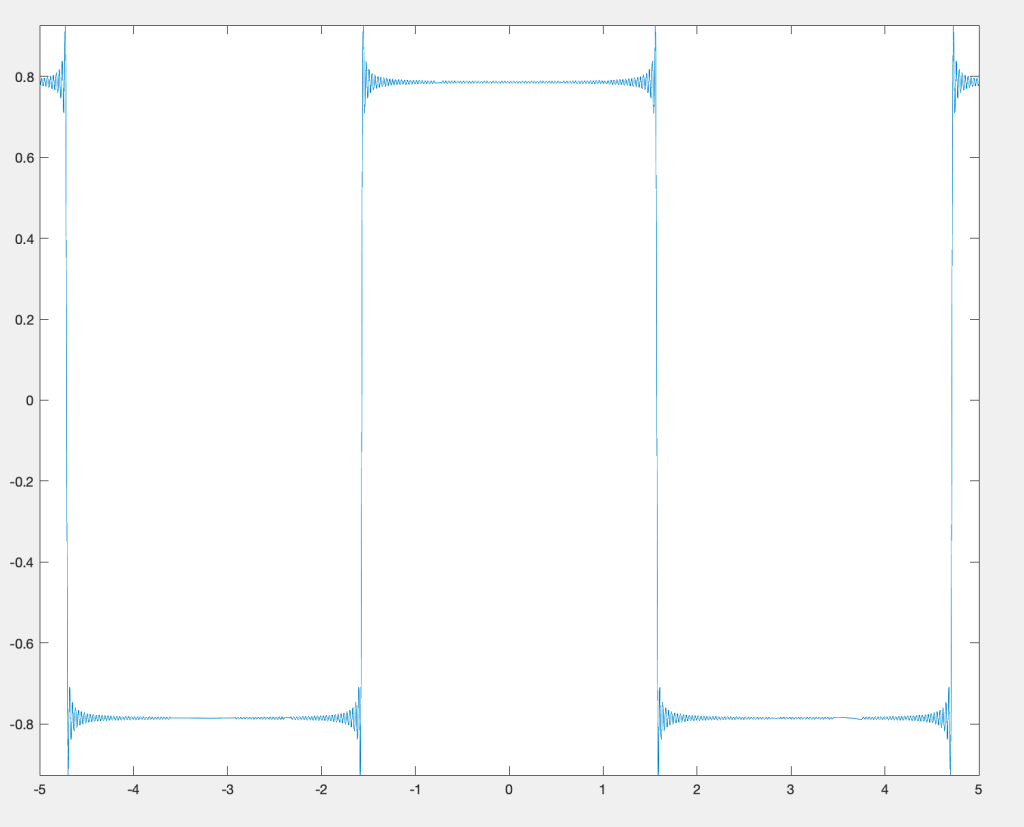

Of course, the first striking thing about this identity is that the right side depends on , whilst the left does not. This immediately raises suspicion – as it should, since the identity is not actually correct. Before delving into the derivation, let us approximate the right hand side with some software to see how wrong the identity is. We can use the following in Matlab:

test = @piover4

figure

fplot(test,[-5 5])

function f = piover4(x)

f = 0

for i = 1:100

f = f + ((-1).^(i+1))*cos((2*i -1)*x)/(2*i-1);

end

endClearly, the equation is not exactly correct, but it definitely works over a large range of . By the way, if we want to do this in Python we can use

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as pltdef piover4(x):

sum = 0

for i in range(1,101):

sum += (-1)*(i+1)np.cos((2i-1)x)/(2*i-1)

return sumxx = np.linspace(-5,5,1000)

yy = piover4(xx)

plt.plot(xx,yy)The two different values the series converges to over most of the are probably not too concerning – those are just sign reversals in the series, and we’ll probably see what’s going on there during the derivation. What is much more interesting are the errors near the discontinuities. For the moment, we will park that discussion, although it turns out to be very important. In the next post, we will look at Fourier’s derivation of the identity, and figure out why it’s wrong, but also kind of correct.